Brazilian Amazon deforestation is commodity driven

Large-scale agricultural activities are the main drivers of deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon.

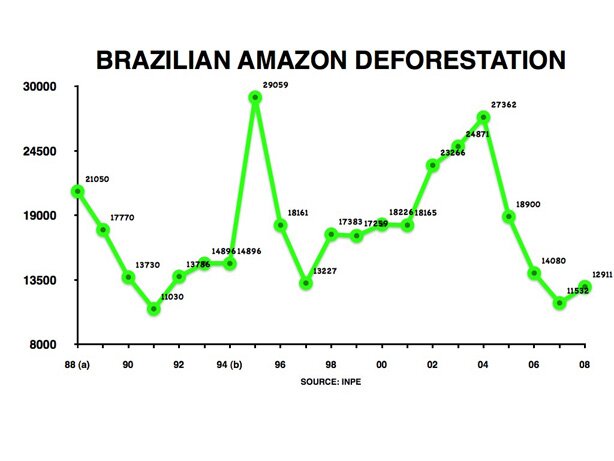

Sergio AbranchesThe Brazilian Institute for Space Research (INPE) last adjusted figures for deforestation, based on satellite data, are mostly bad news for the Amazon(in Portuguese, unfortunately requires subscription, and here for a descriptive note in English). Deforestation has increased in 2008, after falling for 3 years.

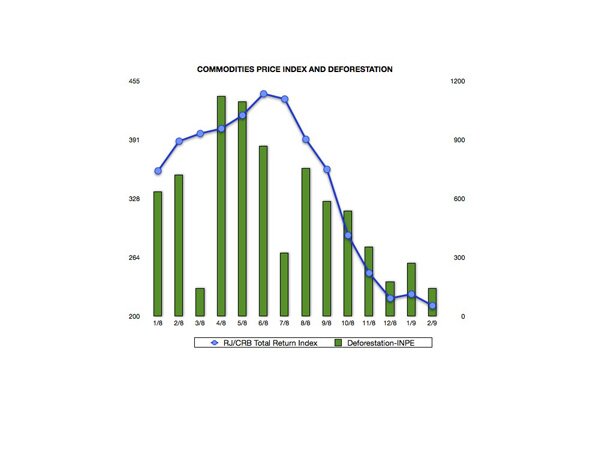

The circumstances of this upturn are relevant to understand the dynamics of deforestation in the Brazilian. It happened on a year marked by an economic downturn on the second half. The government’s command and control activities were not discontinued, although they may have been somewhat reduced. The moratorium on soybean exports from land cleared after July, 24, 2006 was apparently being enforced by major trading companies. A decision by the National Monetary Council forbidding official credit institutions to finance activities on properties without proper land tenure certification and Ibama’s (the Federal environmental agency) license was also in force. It should be noted, though that economic deceleration, due to the global financial crisis, was preceded by a commodity price bubble.

Deforestation has increased significantly in spite of these apparently adverse conditions, and has also changed its geography. INPE’s president Gilberto Câmara, @gcamara, tweets say that deforestation has migrated from the so-called “Arch of Deforestation”, an area comprising southeastern Pará, northern Mato Grosso and Rondônia, moving to the core areas of Pará and Maranhão states. Deforestation has become more scattered and difficult to foresee and control, another of his tweets concludes. This migration notwithstanding, the two major axes of deforestation continue to be the “Middle Earth”, state of Pará, between the Xingu and Tapajós rivers, and the Br-163 road, linking Cuiabá, capital city of the state of Mato Grosso, to Santarém, Pará.

The first chart shows only figures for fully cleared land. Forest degradation has also increased very much, 67%, on the same period. Forest fires, usually associated to land clearing, have also shown a very significant upward trend.

This movement is a clear sign that the problems of governance failure have not been solved in the region, as the government has been claiming since deforestation started to go down. Moreover, the drivers of deforestation continue to be the same as before: large scale agriculture, and extensive cattle raising. The relationship between commodity prices and deforestation still holds. My take is that these activities are not compatible with the goal of stopping Amazon deforestation, and if allowed to continue, they’ll eventually lead to a catastrophic decay of the forest.

No government in Brazil has ever had a project of development reconciling economic activities and forest protection. The present government’s Plan for Accelerating Growth is antithetical to the goal of reducing deforestation, for it is mainly based on road-building, and mega hydroelectric plants. Roads are definitely the major factor of deforestation and those cutting across nearly untouched forest, such as the BR-319, between Manaus, capital city of the Amazonas State, and Porto Velho, capital city of the Rondônia State, lead the way to the opening of new agricultural frontiers.

Carlos Minc, the Environment Minister, has told me that in the areas the Army is paving the BR-319 road deforestation has already been detected, and is increasing at a very fast pace. The Federal environmental agency, Ibama, has rejected the study of the road’s environmental impact, and is asking for a new study. The Environment Ministry has also asked for several precautionary and compensation measures before it issues the license. There is strong opposition, both within the government and in Congress to both requirements.

Deforestation is commodity driven, and roads are not always only a means to carry produce to the ports, but also to clearing of new areas for the expansion of agribusiness. Professor Paulo Fernando Fleury, of the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro, one of Brazil’s most well-known experts on logistics has told me that his analysis of the economic production of the BR-319 Road shows it is the modal having the worst cost-benefit result. The best cost-benefit, in strictly economic terms, would be the waterway. Accounting for environmental hazards, the railroad would be the best choice, although considerably more expensive than the waterway, that needs only some improvement investment.

The chart plots the Reuters/Jefferies CRB Index of Total Return, measuring commodity prices, and INPE’s deforestation figures for 2008 and the first two months of 2009. The correlation is quite clear. A finer analysis would require a larger time series, some correction for seasonal variation of deforestation data, because of the wet-dry periods, and an analysis of possible lags between prices and land clearing. Anyway, there is little reason to doubt that what lies behind Amazon deforestation is an economic logic. This economic logic responds to large-scale activities, and to export activities. Only actions that hit directly these economic agents, either from the demand side – such as a ban from large customers, as recently happened with beef and leather – and government economic sanctions against large corporations found associated to deforestation and forest degradation will stop this drive. Ultimately a durable, or sustainable, solution for the Amazon will require the replacement of these high-risk activities by value-added, science and technology based activities, that generate more quality jobs and income to the population, and help to protect the forest.

Tags: Amazon, Brazil, commodities, deforestation